Everybody has a first obsession. Mine was Disney’s Sleeping Beauty (1959), which I first saw when I was three. As a medievalist, as a lover of classical music and ballet, and as a fan of fairy tales and book arts alike, I love Sleeping Beauty, and I always will. Add it to the (small) list of hills I will die on.

Watching it recently with my four-year-old daughter, however, was cringeworthy. Even if the resulting Twitter thread was one of my more popular contributions to social media.

I know I’m not alone. Those of us with children look forward to sharing books or movies we loved as kids with them. Growing up, I was a ‘princess girl’. And if the constant Elsa chatter is any indication, my daughter is too. But, is it possible to enjoy this film with a child, knowing just how dated the gender politics are? And, follow up question: as a parent, is there a way to share this with their obsessive sponge-brains and not have them absorb lessons about women being passive vessels of white heteronormativity?

Short answer: Yes. It takes a bit of recontextualizing and some resistant reading, but it can be done. And believe it or not, both of these are well within a four-year-old’s capacity. It might even be within yours.

Once Upon a (Medieval) Dream

There are two major elements that set Sleeping Beauty apart from other Disney princess offerings. Both are connected to the film’s curious relationship with the Middle Ages.

First, the animation style is…unique.

For the full, immersive, experience, I recommend watching the full 2min clip, but if you just want the general idea, start at 0:57.

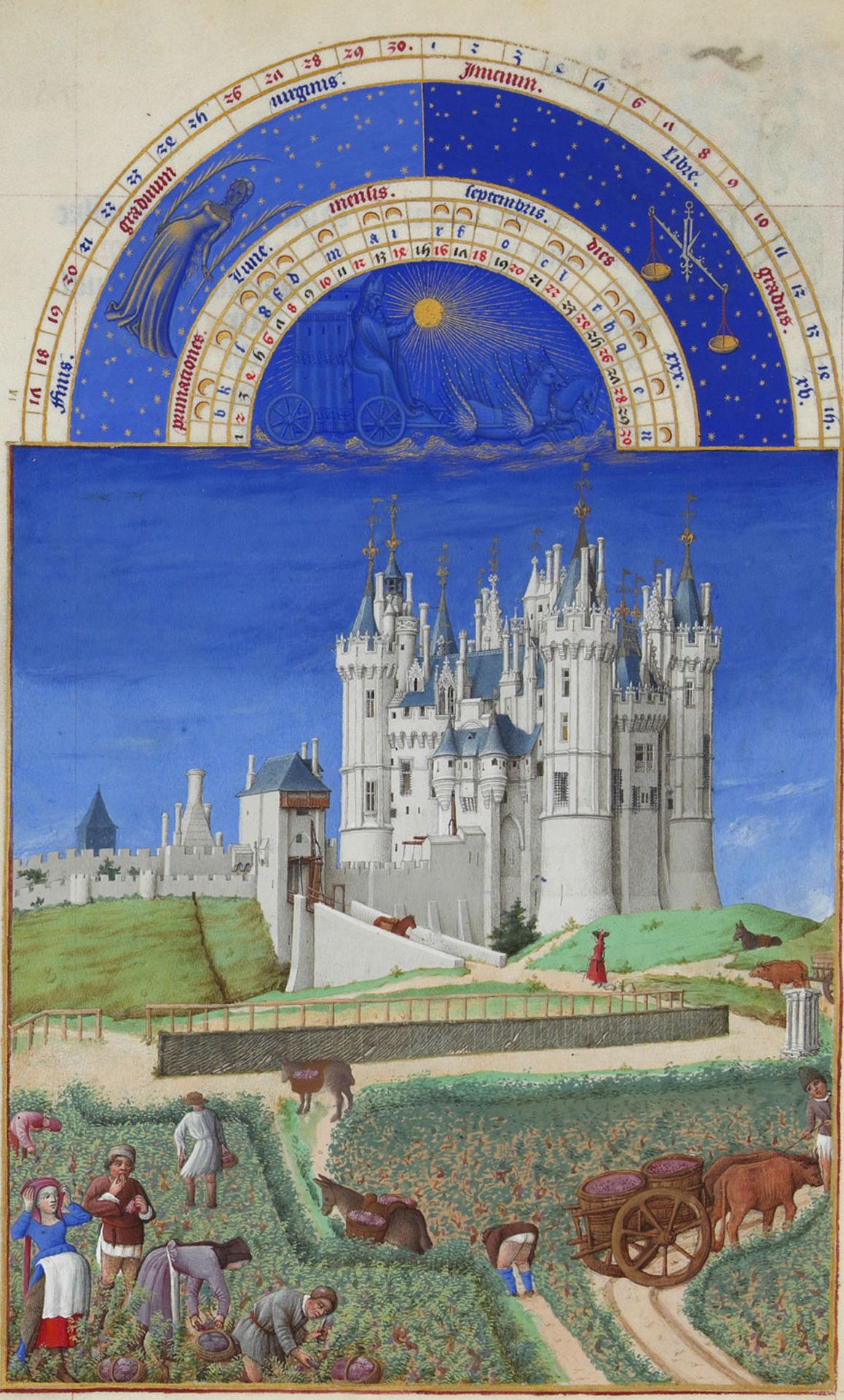

People who don’t like this style call it ‘flat’ or ‘unrealistic’. But, to me, that’s part of the point. It looks like a medieval book come to life.

This is, in fact, exactly what Walt Disney was going for. As Sleeping Beauty was being created, he ordered designer Eyvind Earle to create ‘a moving illustration’ when animating the film. It is full of grace notes and flourishes that have nothing to do with the (paper-thin) plot. Characters randomly burst into rhyming verse. Banners and backdrops feature actual medieval heraldry, like the two-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire. One character informs another that ‘you’re living in the past! This is the fourteenth century!’ Two kings and a minstrel get extremely drunk and one hits another with a fish ten years before Monty Python made it fashionable. Overall, these flourishes create a world that is meticulously, self-consciously, medieval.

Of course, what Walt Disney believed to be ‘medieval’ owes more to nineteenth century adaptations of the Middle Ages than to the actual medieval period. For example, the iconic Disney castle is based on Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, which is not medieval at all—unless you count the foundations. There was a medieval castle there, but it was razed to the ground and a new one was constructed on the site in the Gothic Revival style between 1869 and 1886. Disney’s first full-length animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, is very medievalesque in style. But the source material for Snow White is a much earlier story, collected by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm and published in multiple editions between 1812 and 1857. Paul Freedman defines Disney’s medievalism as

[A] ‘medieval-ish’ past of adventure and romance is populated by good protagonists who exemplify self-determination, opportunity for all and enthusiasm about the future.

Freeman calls Disney’s way of looking at the Middle Ages ‘retroprogression’—a way of looking back at the past not to escape into it but to draw from it:

Retroprogression means that the past offers escape into fantasy in order to draw lessons for the present and promote confidence about what is to come, not to create a sense of vanished magic.

Sleeping Beauty definitely reflects this attitude, and not just because Aurora’s dresses better fit 1950s fashion than 1350s or 1450s.

This is not the solemn nostalgia we see in works like Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, where characters are constantly pining for a world long gone. Sleeping Beauty is full of colour—pastels and jewel tones pop all over the screen, in costumes, banners, and even forest creatures. The backgrounds are intricately detailed, like manuscript borders or tapestries.

Or, alternately, the medieval-inspired work of mid-19th-century artist and leading member of the Arts & Crafts Movement, William Morris.

The second thing that makes Sleeping Beauty unique within the Disney princess canon is the soundtrack. Unlike the films of the ‘Disney Renaissance’ (from 1989–1999), with their familiar sequences of earworming musical numbers, there are maybe four actual songs (i.e., sung pieces of music, rather than just instrumentals) in Sleeping Beauty. I might even say fewer, since background choruses and the kings’ drinking song barely qualify. But the instrumental music is an arrangement of the 1889 ballet version of Sleeping Beauty by Peter Ilych Tchaikovsky.

The film therefore blends medieval visuals—or at least, visuals drawn from reinterpretations of the Middle Ages with the stylistic eye of the late 19th to mid-20th centuries—with the lush orchestrations of nineteenth-century Russian ballet. It’s that kind of conscious anachronism (think Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo and Juliet or A Knight’s Tale) that first grabbed my attention as a kid, and that still fascinates me as an adult.

“You can’t marry a man you just met.”

With my love for the film firmly established, let’s move on to the problems.

Far from Moana, Merida, Elsa, or Anna, Princess Aurora is maybe the least active Disney princess. She spends the first third of the movie as a baby and the final third asleep. In between, she hangs out with woodland creatures and sings. She also falls in love with a complete stranger (Prince Philip) after dancing with him for less than the length of a chorus.

Don’t get me wrong. ‘Once Upon a Dream’ is beautiful—one of my all-time favorite Disney songs, in fact (and I have a soft spot for the spooky Lana Del Ray version too). But Aurora is sixteen, raised in the woods, and completely naïve. She acknowledges that Philip is a stranger; she doesn’t even know his name. But she immediately decides she’s in love with him, and nobody questions it. That’s a bit too close to Bella Swan for my comfort.

My daughter, thankfully, finds the thought of marrying a stranger laughable. For that, I have to credit the Frozen films—for all their flaws, they push back on that particular trope. Princess Anna does not end up with the seemingly perfect Prince Hans, who she meets (you guessed it) at a royal ball. Instead, Hans turns out to be a charming grifter, and over the course of not just Frozen but last year’s sequel, Anna forms a lasting relationship with Kristof, a man who listens to her and values her. I appreciate this.

At the end of Sleeping Beauty, Aurora’s prince finds her asleep. He kisses her without her consent to wake her up. The audience is supposed to trust from a brief, wordless, smile that she’s content to spend the rest of her life with him. While we don’t see an actual wedding, the film ends with them kissing on a cloud, surrounded by angels; that seems pretty cut and dried to me.

In fact, Aurora does not speak a single word in the entire second half of the film. How do we know anything about her motivations or her desires? Do they even matter? The man she supposedly falls in love with just happens to be the same one her father intended her to marry all along for political reasons. It’s all so very convenient, as if it were a man’s idea of how a princess would react to an arranged marriage.

You may think I’m overreacting. After all, it’s just an old-fashioned fairy tale. We all know how they work. But it’s one thing to deconstruct fairy tales with my college-aged students, and another to watch my small child grapple with antiquated societal norms that are the opposite of how I want her to live her life.

How To Talk To Your Kids About Old-School Disney, Part 1: Sources

I’m figuring out how to help her understand. We’ve had several discussions since then (because as any parent knows, a child never watches a Disney film just once). She’s interested in the fact that there are multiple versions of the story, and that some of them, including the Disney version, were made many years ago when people had strange ideas about what women should and shouldn’t do. (My daughter, incidentally, enjoys having her Elsa, Anna, and Wonder Woman dolls fight ‘the patriarchy’, so she’s at least got that down.)

First, we talked about the movie’s context, source material, and adaptations—simplified for a four-year-old’s understanding.

For those looking to have this conversation with your own children but who don’t spend their time reading multiple versions of fairy tales, here’s where the story comes from. Disney’s film is based on the 17th century tale ‘La belle au bois dormant’ (‘Sleeping beauty in the wood’) by Charles Perrault.

Perrault’s telling lost several of the more hair-raising elements from earlier versions. Giambattista Basile’s version from a century earlier has the heroine wake not with a kiss but with the birth of her twins; she was raped during her enchanted sleep (and, before you ask, I did not include that detail in the discussion with my daughter). Somewhat less hair-raising is the ‘Ninth Captain’s Tale’, an apocryphal story from the Thousand and One Nights, which specifies that the sleeping princess is only ten years old(!) but wakes her with the removal of a stick of flax from behind a fingernail, rather than a kiss. As with most folktales and fairy tales, we do not have an ‘original’, only multiple early versions with elements in common.

But Disney, being Disney, made several more changes.

In both Perrault’s story and Tchaikovsky’s ballet (the scenario—i.e. the plot—written by Ivan Vsevolozhsky), Princess Aurora is raised at court, the only royal child and heir to the throne. One of the most famous movements in the ballet is the Rose Adagio in the first act. In it, Aurora considers several marriage proposals at her sixteenth birthday party, before wandering off and encountering an inconveniently placed spinning wheel. This portion of the ballet also includes the ‘Garland Waltz’, which eventually became ‘Once Upon a Dream’.

The film, however, sees the princess spirited away by the three ‘good’ fairies and raised as a foundling in the middle of a forest. The fairies claim this is for her safety, and all we hear of her parents’ response is that they ‘watched with heavy hearts as their most precious possession, their only child, disappeared into the night’.

And then, the King and Queen just…wait. For sixteen years. No explanations, no updates, nothing. (Also, referring to their child as a ‘possession’ is…ugh.)

This was the plot point my daughter really had a problem with. The film calls them ‘good fairies’. But after some discussion with her dad on the topic of parents allowing three near-strangers to make off with their newborn child, she now refers to them as the ‘thumbs-sideways fairies.’ And as we talked it over, she found it interesting that this part only appears in the movie, and not in any of the other versions of the fairy tale.

So, in the end you may find that your kids understand different versions of stories, and their changing social contexts, better than you expect.

How to Talk to Your Kids About Old-School Disney, Part 2: Getting Medieval

Aurora in Disney’s Sleeping Beauty is actually a common plot device: a ‘Fair Unknown’. A ‘Fair Unknown’ is a seemingly ordinary character whose true identity is kept from them by supernatural means until the plot demands that it be revealed. This plot device only appears in the Disney version.

Where it does appear is in a particular type of medieval literature: the romance. Not to be confused with romance novels (though they share some commonalities); medieval romance is a precursor to the modern fantasy genre—full of battles, family conflict, relationship drama, and supernatural encounters. Arthurian legend, for example, is filled with fair unknowns. King Arthur himself is one in many stories—stolen away as a baby by the sorcerer Merlin and only identified as the rightful heir to the throne when he draws an enchanted sword from a stone (in fact, Disney made a film about him just four years after Sleeping Beauty).

Watching Sleeping Beauty as an adult, it is clear that the film isn’t actually about a cursed princess and a spinning wheel. For all that she is the headliner, Princess Aurora isn’t the protagonist. There is a history—a long one—between Aurora’s three guardians (Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather) and that most iconic of Disney villains, Maleficent.

There are multiple references to earlier clashes between them, and the fairies are desperate to stay ahead of her, rarely if ever taking human concerns into account. The humans in the story—the king, the queen, Princess Aurora, and Prince Philip—are all their instruments, and without the fairies’ manipulations, there would be no plot.

The 2014 live-action film Maleficent gestured in this direction, although it diminished the role of the three fairies, making the king into Maleficent’s antagonist. But even that supposedly feminist reworking falls into predictable, tired stereotypes about motherhood and agency. In many ways, the original Maleficent is more satisfying, wielding her incredible powers with all the style, confidence, and inscrutability of Morgan le Fay or the Lady of the Lake. Lord, what fools these mortals be.

Stories of mortals living at the whims of powerful magicians can be found all over medieval romance, not to mention in later works like William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (quoted above) or Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene. Magical practitioners in these stories are often enormously powerful, blinking in and out of plotlines to either solve mortal problems or create new ones—and sometimes both at once.

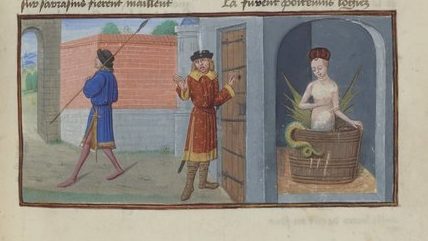

The 14th century Roman de Mélusine, for instance, tells the story of a powerful fairy cursed to transform into a snake once a week. She agrees to marry a young nobleman on the single condition that he never enter her room on Sundays. Her magic allows her to construct castles out of thin air and make her husband the wealthiest man around, but that doesn’t stop him from spying on her and breaking his promise. Even though their marriage ends poorly, the romance tells us that their bloodline lives on in the noble house of Lusignan (not to mention, more inexplicably, on the Starbucks logo).

My daughter was more interested in the fairies than in Aurora, even if a lot of that interest involved hypothetical conversations where the king and queen sent them packing and held onto their baby girl. What she has decided to stick with, however, is the soundtrack. I can’t say I mind that ‘Once Upon a Dream’ is now the biggest hit in the bedtime lullaby circuit for both her and her younger sister. But my conversations with her reflect her ability to take apart and question the media she’s consuming rather than just swallowing it without question.

Conclusion: Visions are seldom what they seem

To some extent, having children is about reliving one’s own childhood. And, sometimes, that means realizing that something you loved as a child is…not so great. But that doesn’t mean that classic Disney needs to be cancelled altogether.

Kids are more aware than we realize of the difference between real and imaginary, so emphasizing the story elements and how they fit together, by comparing different versions of the same story, can help children think more critically about what they’re watching or reading. It makes them think about who is creating, or adapting, the story, and why they made the choices they did. Given how much media kids consume these days, talking to them about it regularly can make a huge difference in how they interact with it, and give them valuable critical thinking skills not just for school but for life more generally.

In the alternative, you can enter the imaginary world and actually engage with their many (so, so, so many) questions about internal logic. Why do the king and queen let the fairies run off with their baby? Why is Maleficent so furious about one missed party invitation? If Fauna can’t cook (as Merryweather claims), how did they feed Aurora in the woods for sixteen years without magic? If my kids are any indication, the questions are endless, and the answers are often hilarious.

And if all else fails, it does make for a good Twitter thread.