By Amy S. Kaufman.

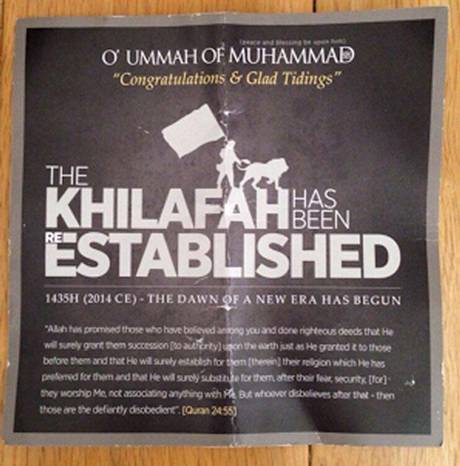

As the self-proclaimed ‘Islamic State’ continues to dominate headlines, medieval scholars have cautioned against casually labeling ISIS and its practices “medieval” as a way of calling them brutal or cruel or to distance them from ourselves. Although ISIS courts the label through its desire to ‘rebuild’ an Islamic caliphate, Clare Monagle and Louise D’Arcens point out that their vision of the Middle Ages is a fantasy, one that “bears little relationship to the historical record of the very complicated and diverse forms of Islamic governance that evolved in the Middle East and around the Mediterranean.”

These are important historical correctives, but there may also be a danger to limiting our conversations about ISIS and the Middle Ages solely to questions of accuracy. If we want to understand the movement’s appeal, especially to Western recruits, we need to consider another dimension of ISIS’s identification with the medieval past: the power that our collective fantasy of the Middle Ages has to inspire violence.

ISIS’s desired caliphate has historical precedent, but the movement also attempts to purify the past, fetishizing a lost “golden time” of Islam as an era free from dissent, free from bid’ah (heretical innovation), when women were silent, obedient, and pure and the entire community hummed with religious synchronicity.*

What is so appealing about this dream of a neomedieval Islamic state to young Westerners? Recruits in propaganda videos claim that ISIS offers them the freedom to be themselves, to live uninhibited lives, true to their hearts. A propaganda video released in June courts young men who feel alienated or constrained, one of its speakers promising, “All my brothers living in the West, I know how you feel in the heart, you feel depressed. The cure for the depression is jihad.” Another speaker on the video, a British man, explains how it felt to leave his wife and children to join ISIS: “I don’t miss a thing, you know?. . . I felt like I was in prison in that country and I’m here. I feel free, you know? I can drive, I can, you know, I don’t need a license. I don’t need insurance. I don’t need this and that…all of these things, you know, you feel like you’re in prison. You’re being punished. Here, it’s freedom. Totally freedom. I can walk around with a Kalashnikov if I want to, with an RPG if I want to.”

Gun- and sword-toting, freedom-fighting, uninhibited, these young recruits cast themselves as heroes in a glorious narrative of revolution and conquest.

A New, ‘Medieval’ Manhood

ISIS is also peddling masculinity through its medievalism—not a historical masculinity, but the brutal Vikings plus Game of Thrones plus a dash of Grand Theft Auto medieval masculinity that’s glamorized in popular culture: a virile, violent, and dominant masculinity that controls the world. And while this wasn’t the reality of the Middle Ages, this is the reality of our fantasies about the Middle Ages, from HBO and The History Channel to Florida Congressman Steve Southland, whose recent invitation to an all-male fundraiser read, “Good men sitting around discussing & solving political & social problems over fine food & drink date back to the 12th Century with King Arthur’s Round Table.”

Obviously, in this neomedieval dream vision, freedom isn’t for everyone. The ‘emancipation’ of ISIS fighters relies on the oppression of those who would complicate the narrative of the golden time: it requires the submission and containment of women (or their rape and enslavement), the slaughter of heretics, and the conversion or execution of unbelievers.

That’s because the draw of the neomedieval state really isn’t about feeling “free”—it’s about feeling powerful and entitled. Even as medievalists lament the stereotype of the Middle Ages as barbaric and oppressive, governed by crushing religious intolerance and patriarchal domination, popular representations suggest that this fantasy of the past has an allure beyond making us feel better about our own progress. A society based on domination implies that someone had the power. And there are those who believe a hierarchy organized by gender and faith is a ‘natural’ or ‘pure’ condition, and more importantly, a structure in which they would have been privileged. They feel that today’s environments of equity and religious parity are landscapes of deprivation that have robbed them of the legacy of leadership and power they deserve.

Salacious Fantasies

Despite the religious claims of a group like ISIS, their fantasy is not the product of Islam. The neomedieval patriarchal religious state beckons with the promise of a lost status reclaimed, appealing both to people who are marginalized, like many first-generation Muslim immigrants, and those who simply see themselves as marginalized, like the Americans who flocked to the Biblical Patriarchy Movement (a movement now shaken by abuse scandals) hoping to ‘take back’ America and create a neomedieval state for Christians; or like Anders Breivik, the Norwegian mass-murderer who claimed to be a Templar warrior fighting against Marxists and Muslims. Or we could cast back further into history for examples of the violent will to regain an imagined medieval power, authority, and grandeur: to the “Knights” of the Ku Klux Klan, for instance, or to Nazi Germany.

I’m grateful to my fellow medievalists for their efforts to keep the media and the politicians honest, and we need more of it, especially when media outlets participate in ISIS’s construction of reality by calling murders “beheadings” and rape victims “concubines” or “sex slaves,” words with salacious rather than horrifying connotations. But we can’t be too quick to dismiss this vision of the past as just a fantasy: it is powerful enough to draw converts and recruits, and to justify violence and persecution in the minds of ISIS fighters. Murder becomes a way of negotiating perceived loss, victims become the agents of a corruption that must be purged, and the legions of innocent dead are celebrated as conquered enemies who threaten a historical precedent that never really was.

ISIS’s fantasies should remind us that the Middle Ages is never just the past. Their dark dream of medievalism, constructed half by history and half by desire, thrives in our collective imagination and threatens to cast a long shadow over our future.

*Peter ‘Theo’ Curtis, writing as Theo Padnos, delves into the intellectual and emotional roots of Westerners drawn to fundamentalist Islam in his 2011 Undercover Muslim: A Journey into Yemen. Students at the Yemeni school he investigated were drawn to the vision of the Islamic “golden time” in the early Middle Ages as well as the possibility of recreating it.

Excellent and thorough article.

I think people want to call this sort of thing “medieval” because they want to distance themselves from it. I’d assume there are a lot of people living in Western societies who think that since they themselves can’t see any “medieval” violence around them, and that it’s largely unheard of or easy for their demographic to ignore on a national scale, that the rest of the world is either the same, or stuck centuries in the past. So perhaps people don’t want to acknowledge that these sorts of things are really happening in the world at this current time, because admitting to yourself “this stuff is happening in our present” is a short step from having to admit “I need to get up off my ass and do something about it”.

Not that people are really saying that, but I’d bet it goes on subconsciously.

The salaciousness of media accounts of ISIS and their atrocities is deliberate. Salacious news keeps people riveted to the TV screen. Unfortunately, it also rots the minds of the viewer into seeing their world as some kind of unironic parody of itself.